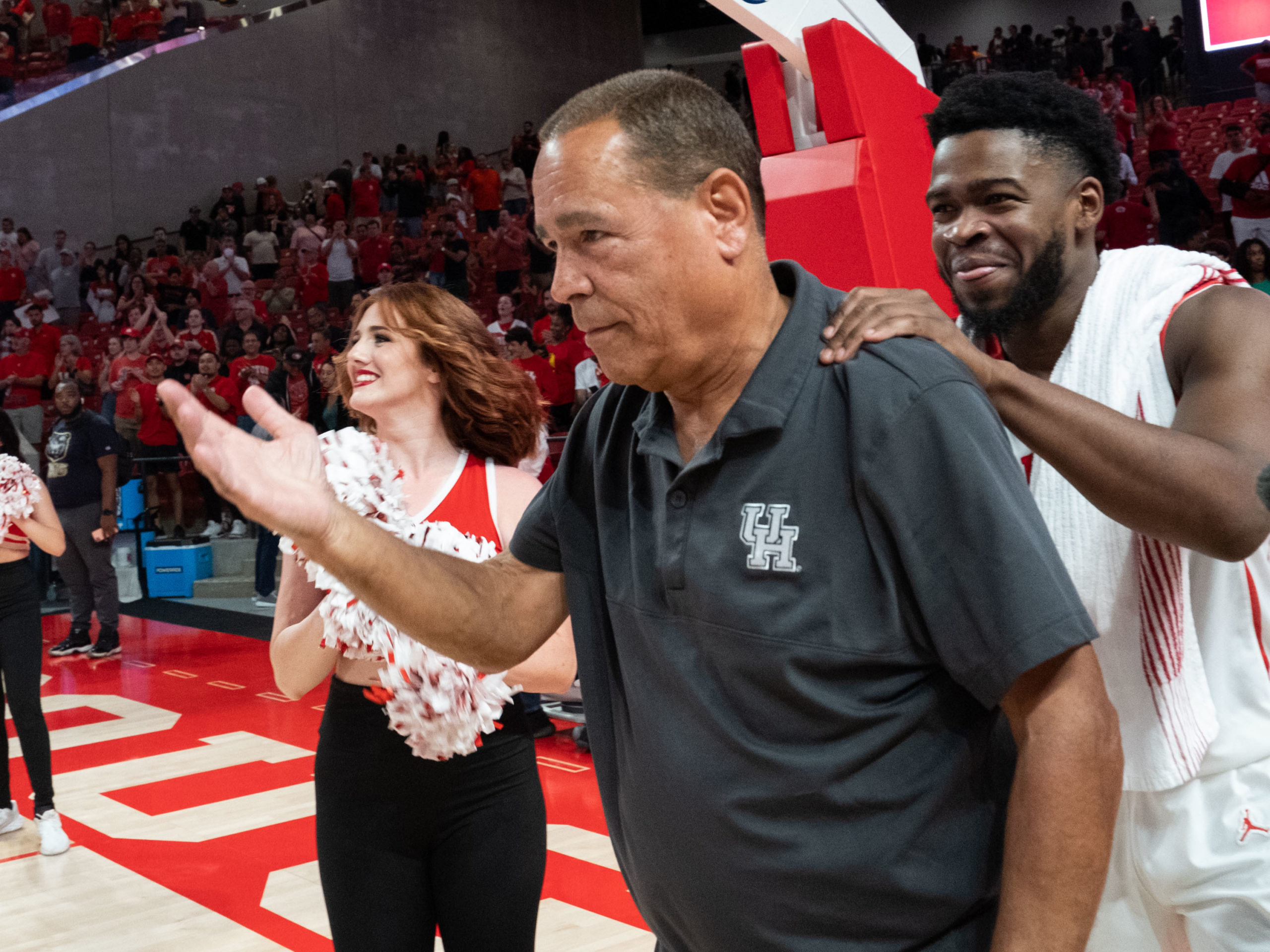

As we enter the nation’s most exciting sports tournament – the NCAA’s “March Madness” – we are faced with a huge elephant in the room. The NCAA’s most important, impactful coach is American Indian (Indigenous) – Kelvin Sampson. His father was a coaching legend in the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina in the 1950s. Now, in 2023, he (Kelvin) is coaching the top ranked (#1) NCAA Men’s basketball team, and he is positioned to be the first American Indian national championship coach in Division 1 NCAA basketball history.

The more I say this out loud – that an American Indian person is, yet again, the BEST in American sports – the more I am reminded of how Indian athletes like Jim Thorpe have been proactively disappeared in contemporary media. Look at any sports show that discusses basketball, football or baseball. Not only are American Indian people not placed in positions of journalistic authority, we are not present to remind the world that we are the best athletes and coaches.

Look at the history of running in America. The famous “Heartbreak Hill” in the Boston Marathon isn’t the story of a White runner who overcame. It is, in reality, the story of a Narragansett runner, Ellison Brown, who dominated non-Native competitors.

I often say that the American baseball mafia – yes, I call them a “mafia” – have persistently ignored American Indian baseball players in North Carolina, New York and California. During my years living and teaching around Los Angeles, I heard several stories of White high schools who, donning Indian mascots, played American Indian baseball players from local boarding schools. The outcome? Well, in the words of one Indian man in Orange County (who I met at a powwow): “you never hear about them because the Indian boys embarrassed the White teams”.

We are at a crossroads. American Indian peoples are perpetually imprisoned in two ways.

- Indian mascots don’t allow American Indians to fully exist as human beings. Not only do those mascots press non-Indians to see American Indians in some sort of ancient savagery, they suffocate conversations about the perpetual greatness of American Indians in sport.

- American Indians are not allowed to narrate American sports and to guide the politics of American sports.

I thought about that last year as the PGA underwent pressure from the LIV Golf (a golf tournament funded by the royal family of Saudi Arabia). As PGA players and officials were wringing their hands – stressing about the future of American (and global) golf – one of the most calming voices on the American golf scene was Notah Begay, a PGA veteran from the Navajo Nation and close friend of Tiger Woods. Begay recently announced that he will begin to truncate his role within golf media as he enters back into competitive golf play. In this moment, I am wondering: “Who is the next Begay? Why aren’t sports media companies looking for American Indian players to tell the story of golf…and of sports, more generally?”

Every day, on ESPN. I watch White and Black commentators debate every sport from basketball, to football, to golf, to swimming. I listen to year-long debates about Black coaches attempting to obtain coaching positions in a White-owned NFL. I watch commercials from the NFL that appeal to Latino audiences by placing Latino and Latina actors into “Chiefs” jerseys and face paint. Though American Indian people have brilliantly moved through a sports landscape in which sports oligarchs prefer Indian people hanging on banners (as a mascots/team names) to Indian people hanging up banners (as star players, coaches and owners), we must be placed into positions of sports media influence.

Jim Thomas, a Lumbee architectural developer, used to own the Sacramento Kings. He didn’t make it a big deal that he is Lumbee (that he is American Indian) because American Indian people often govern the everyday workings of American life … quietly. Look at Jim Thorpe who was, at one time, the commissioner of the NFL. Look at Notah Begay. Look at Kelvin Sampson. They speak, but they aren’t loud. They are polite. They endure seeing themselves dehumanized. They might not expect to be celebrated. (But they should be celebrated.)

While they have made American sports work, they are not allowed to be heralded storytellers. They are not given national and global megaphones that would allow them to let their Indigenous worlds –the Indigenous worlds that molded them and have given them brilliant insights in their playing and coaching (and owning) – reorganize and humanize American sports and American society, more generally.