https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2022/11/12/peabody-hair-samples/Over the last few days and weeks, pressure has increased across the United States as a case involving ICWA – the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 – is before the Supreme Court of the United States. This case was originally written as a response to the stealing of American Indian children across the United States through child welfare practices that disguised themselves as protection for Indian children. In reality, these practices provided a “license to steal” that began with the theft of Indian land through various such as the Morrill Act of 1862. Indian elders across hundreds of American Indian nations state that there were times when their communities had practically no children running around. By 1978, Indian people had become tired of government agencies and church organizations placing pressure on social workers and local police to apprehend children and separate them from their family and kin.

The work of American Indian people to take back what colonialism has taken from us often revolves around our children. Recently, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum announced that it was returning the hair “samples” of over 700 American Indian children. These hair clippings were taken from children who were imprisoned within boarding schools across the United States by anthropologist George Woodbury.

When this story became national news, I noticed something. News agencies across the United States – the New York Times, MSNBC, Time Magazine – had no American Indian journalists to tell the story. They operated as if there were no Indigenous peoples to tell America’s stories.

The theft of American Indian children – into boarding schools and within the conditions of hair “samples” and other anatomical members in museums – is sewn together with American pop cultural stories that act is if Indigenous childhood is not under perpetual attack. Disneyland and Disneyworld place Latina and Asian women into faux-leather skirts at the entrance to their parks. These women are perhaps 25-30 years old. This adulting of Pocahontas hides the fact that the real Pocahontas was 16 to 17 years of age when she was forced to marry and have a child with John Rolfe.

If we zoom out, we see the United States and Canada as perpetual attempts to physically and emotionally harm Indigenous children. In July 2022, Pope Francis of the Catholic Church issued an apology for decades of sexual abuse of Indigenous children in Canada. When the movie “Spotlight” came out in 2015, producers ended the film with a rolling list of places where priests sexually abused children before they were hidden in the Boston diocese. Many of these places of abuse were American Indian communities/reservations across the United States.

Colonial abuse of Indigenous children might seem less intimate. It swirls around in the air and water. It is captured in plausibility deniability – in the ability for government officials and corporate executives to state without flinching that they have done nothing wrong. That is the case with energy corporations, like Duke Energy in North Carolina, who have systematically targeted American Indian lands and lives across the United States and Canada.

In late 2019 or early 2020, I drove my niece across the Lumbee Tribal community in Robeson County, North Carolina. I thought she was watching Disney’s Moana on the in-car monitor. Suddenly, she opened up and spoke: “Uncle…why are all the trees gone?” As I looked to the side of the road, there were massive tunnels of emptiness between large sections of trees. The trees that had been cut down were laying on the ground. I thought about being careful with my response. However, I went all in: “Well, these trees are profitable for people in Europe who use them for fuel. And in their place, the chicken companies will put up big chicken houses to feed people around the world.” She told me that she did not understand why we had to lose our trees. No one needed to use wood pellets for fuel. No one needed chicken so bad that our community had to be filled with chicken houses.

I reflected on our conversation for a few weeks. I realized that what my niece saw in the form of disappearing trees – in the form of millions of chickens that created toxins that filled her lungs – was a testimony of the absence of American Indian people in positions that dictated what left and entered her world. Environmental agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is led by non-American Indian people. Courts that decide when and how corporations can pollute American Indian land (with gas infrastructure and chicken farms that are three-times the size of a football field) are not directed by American Indian judges.

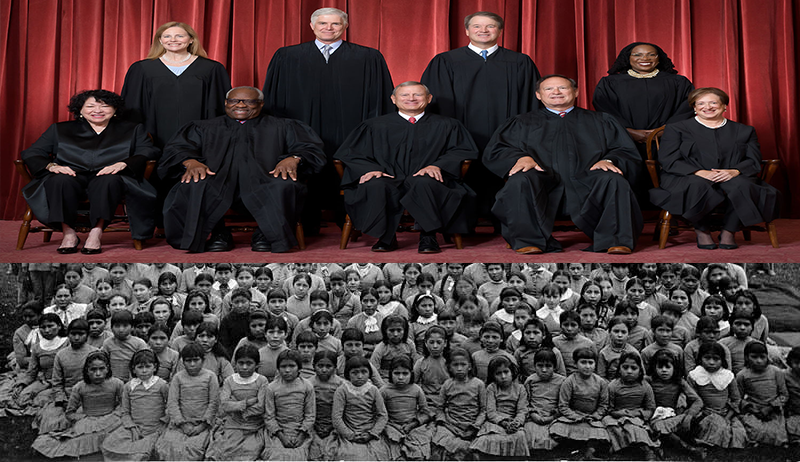

Indeed, this is the proverbial elephant in the room as we wait for the Supreme Court of the United States to decide on ICWA. American Indian people are only present as the people who are asking the court to protect the authority and dignity of American Indian people. “The court of the conqueror” – what Chief Justice called the Supreme Court of the United States in 1823 – is a diverse consortium of Indigenous suppression. American Indian peoples hope that a court of non-Indian judges will understand Indian children and defend them.

The reality is that Indigenous children will not be protected until Indigenous peoples determine the world that they live within. Their aunts, uncles and grandparents must be U.S. Senators, Supreme Court Justices and the Deans and Presidents of Universities. The majority of Supreme Court Justices went to Yale or Harvard Law Schools. Do you know what that means? There must be a proactive push within these educational institutions to transform their classrooms into catapults for Indigenous judiciary authority. What if the first American Indian President appointed the first American Indian Supreme Court Justice? Of course, no matter who the President is when the next Justice is chosen, they must choose an American Indian Justice. But, let’s dream. Let’s prophesy. Imagine a State of the Union Address in the near future as a U.S. President speaks in front of a United States Supreme Court that is majority American Indian about their work to return American Indian land – to make America safe for Indigenous children from over six hundred American Indian nations, Alaska and Hawaii. This begins with a reorganization of leadership across governments, educational intuitions and corporations.